As an Amazon Associate CoffeeXplore.com earns from qualifying purchases.

Unlocking Flavor: Does Coffee Have Citric Acid?

Ever wondered what gives your favorite coffee that bright, tangy kick? You might have heard terms like “acidity” thrown around, but what does it really mean, and does a common food acid like citric acid play a role? Many coffee lovers appreciate that vibrant quality, while others might find highly acidic coffees lead to discomfort, making the source of this acidity a key point of curiosity.

Yes, coffee naturally contains citric acid. It’s a significant organic acid found within green coffee beans, recognized for contributing bright, tangy, and distinct citrus-like flavor notes (think lemon or lime) to the final brewed cup.

Understanding coffee’s acidity, especially the role of citric acid, can unlock a deeper appreciation for your daily brew. This guide dives into the science behind coffee acidity, pinpoints the role of citric acid, explores what influences its levels, compares it to other coffee acids, and offers tips for those seeking a smoother, lower-acid experience. Get ready to discover exactly how citric acid shapes the flavor profile of your coffee.

Key Facts:

* Naturally Present: Citric acid is one of the most common organic acids naturally inherent in green coffee beans, according to research highlighted by sources like Trade Coffee and Belco.

* Flavor Contributor: It’s widely recognized for imparting bright, tangy, and often desirable citrus fruit notes (like lemon or grapefruit) to coffee’s flavor profile, as noted by Sweet Maria’s Coffee Library and Sucafina.

* Variety Matters: Arabica coffee beans, particularly those cultivated at higher altitudes, generally contain higher concentrations of citric acid compared to Robusta beans, a point emphasized by Sweet Maria’s.

* Roasting Impact: Citric acid levels decrease significantly during the roasting process. Lighter roasts retain more of this acid, contributing to brighter flavors, while darker roasts feature lower levels due to heat degradation.

* Processing Influence: Washed processing methods are often associated with a clearer expression of citric acidity in the final cup compared to natural or honey processing methods.

What Makes Coffee Acidic Anyway?

Coffee’s acidity primarily stems from various organic acids naturally present in the beans themselves, influencing both taste and aroma, rather than just being a low pH score. These acids, including familiar names like citric and malic acid, are crucial components that contribute significantly to the coffee’s perceived brightness, tanginess, and overall flavor complexity that many drinkers enjoy. Think of it less like stomach-churning acid and more like the pleasant tartness in fruit.

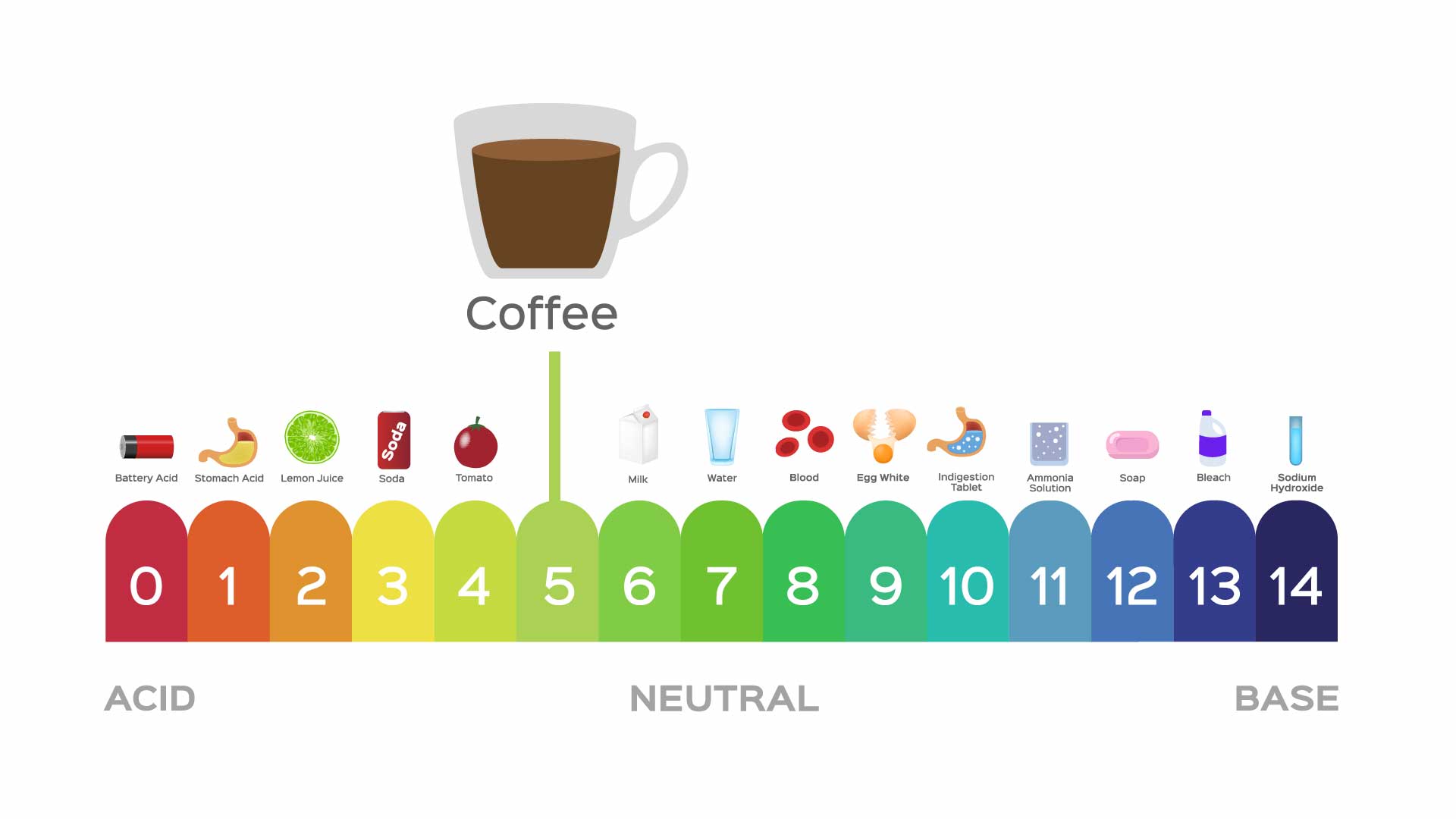

Understanding Acidity vs. pH in Coffee

It’s easy to confuse perceived acidity (the taste) with pH level (the chemical measurement), but they aren’t the same thing in coffee. pH measures the concentration of hydrogen ions, indicating chemical acidity (lower pH = more acidic), while perceived acidity refers to the bright, tangy, and fruity flavors we taste. Coffee typically has a pH between 4.85 and 5.10, making it chemically acidic (neutral pH is 7.0), but the taste of acidity comes from specific organic acids creating flavor sensations. You can have two coffees with the same pH level taste vastly different in terms of perceived brightness or tanginess.

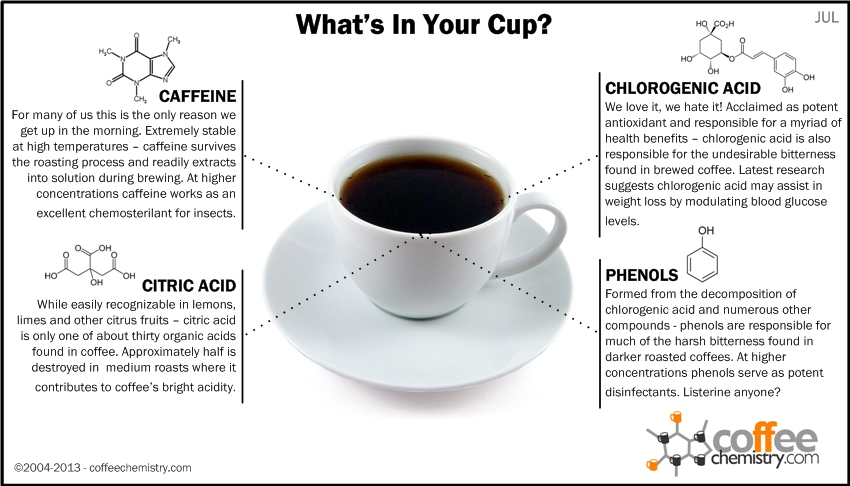

Key Organic Acids Found in Coffee Beans

Coffee beans are complex little powerhouses of chemical compounds, including a host of organic acids. These develop in the coffee cherry and transform during processing and roasting. Here are some of the main players:

- Chlorogenic Acids (CGAs): Actually a group of acids, these are abundant in green coffee and contribute to bitterness and body. They decrease significantly during roasting.

- Citric Acid: As we’ll explore, this acid provides bright, citrus-like notes (lemon, orange, grapefruit).

- Malic Acid: Often associated with the tartness of fruits like green apples or plums.

- Quinic Acid: Increases as coffee degrades (especially during roasting or if brewed coffee sits too long) and contributes to sourness and astringency.

- Acetic Acid: The same acid found in vinegar; in small amounts, it can add a pleasant sharpness or winey note, but too much indicates processing defects (over-fermentation).

- Phosphoric Acid: An inorganic acid that can contribute a sparkling or cola-like sensation, often perceived as sweeter than other acids.

So, Does Coffee Actually Contain Citric Acid?

Yes, coffee absolutely contains citric acid; it is one of the principal organic acids naturally occurring in green coffee beans. Far from being an additive, citric acid is an inherent component that plays a vital role in shaping the sensory profile of coffee, especially contributing to the perception of bright, tangy, and often distinct citrus-like notes in the final cup’s flavor.

Citric Acid’s Role in Coffee Flavor

What does citric acid taste like in your coffee? Citric acid primarily contributes bright, tangy, and refreshing citrus-like notes (think lemon, lime, grapefruit, or orange) to coffee’s flavor profile. Coffees described by professional tasters as having a “clean,” “crisp,” “vibrant,” or “lively” character often owe these qualities, at least in part, to their citric acid content. It adds that high note, the juicy quality that makes certain coffees particularly refreshing.

How Much Citric Acid is Typically in Coffee?

Pinpointing an exact amount is tricky because the concentration of citric acid varies considerably based on several factors, including the specific coffee variety, its origin (altitude, climate, soil), and how it was processed. While it’s a key acid, its levels fluctuate. For instance, high-altitude Arabica beans often boast higher citric acid levels compared to Robusta beans or Arabica grown at lower elevations. Sweet Maria’s notes it’s a key component in “good, bright coffees.”

What Factors Influence Citric Acid Levels in Coffee?

Several key factors influence the final concentration and perception of citric acid in brewed coffee, spanning from the farm to the roaster. These include the bean variety (Arabica generally higher), growing altitude (higher often means more), the processing method used after harvest (washed process tends to highlight it), and crucially, the roast level (lighter roasts preserve more citric acid than darker roasts).

Coffee Variety and Origin Impact

The genetic makeup of the coffee plant plays a significant role. Arabica varieties, especially those grown at higher altitudes like many Kenyan or Central American coffees (e.g., Guatemala, Panama), tend to have naturally higher levels of citric acid compared to Robusta varieties, which often have higher levels of other acids like chlorogenic acids but less citric. This contributes to the sought-after brightness found in many specialty Arabicas. Sweet Maria’s specifically mentions Kenya, Burundi, Guatemala, and Panama as origins where citric acid notes are prized.

Processing Methods: Washed vs. Natural

How the coffee cherry is processed after picking significantly impacts the final flavor profile, including acidity.

* Washed (Wet) Process: Cherries are pulped, fermented briefly in water to remove mucilage, then washed and dried. This method tends to produce coffees with cleaner, brighter, and more distinct acidity, often highlighting citric notes more clearly.

* Natural (Dry) Process: Whole cherries are dried intact, allowing sugars and compounds from the fruit to impart flavor to the bean. This often results in heavier body, fruitier sweetness, and potentially more complex but less focused acidity compared to washed coffees. Citric notes might be present but potentially overshadowed by other fruit flavors.

The Role of Roasting: Light vs. Dark

Roasting is a transformative process where heat fundamentally changes the chemical composition of the bean. During roasting, citric acid degrades as temperatures rise. Consequently:

* Light Roasts: Experience less heat and shorter roast times, preserving a significant amount of the original citric acid. This contributes to their characteristic bright, tangy, and often citrusy flavor profiles.

* Dark Roasts: Roasted to higher temperatures for longer durations, much of the citric acid is broken down. This results in lower perceived acidity, often replaced by roast-derived flavors like bitterness or smoky notes. Quinic acid also tends to increase in darker roasts, contributing to sourness rather than bright acidity.

Key Takeaway: If you enjoy bright, citrusy notes in your coffee, look for light to medium roasted Arabica beans, often from high-altitude Central American or East African origins, especially those processed using the washed method.

How Does Citric Acid Compare to Other Acids in Coffee?

While important, citric acid is just one part of coffee’s complex acidity puzzle. Citric acid provides distinct bright, citrusy (lemon/lime) notes, differentiating it from malic acid’s fruitier, apple-like contribution, and the bitterness/body derived from chlorogenic acids (which decrease with roasting). Meanwhile, quinic acid adds undesirable sourness, especially in stale or dark-roasted coffee, and acetic acid can introduce a vinegar tang if present in higher amounts.

Malic Acid: The Fruity Contributor

Often described alongside citric acid, malic acid contributes flavors reminiscent of stone fruits or, most commonly, green apples. It provides a different kind of tartness – slightly softer and fruitier than the sharp brightness of citric acid. Coffees from regions like Colombia or some parts of Central America might showcase noticeable malic acidity. Sucafina notes it gives a “tart or apple-like taste.”

Chlorogenic Acids: Bitterness and Body

These are the most abundant acids in green coffee but are not typically associated with the pleasant acidity coffee lovers seek. Chlorogenic acids (CGAs) primarily contribute to coffee’s perceived bitterness and body. They break down significantly during roasting – light roasts retain more, contributing potentially to both bitterness and some perceived acidity, while dark roasts have much lower levels.

Quinic and Acetic Acids: Sourness and Vinegar Notes

These acids are often associated with negative flavor attributes, especially when prominent.

* Quinic Acid: Forms as other acids (like CGAs) break down during roasting and as brewed coffee sits and cools. It contributes a sour, astringent, and sometimes metallic taste, often more noticeable in dark roasts or stale coffee.

* Acetic Acid: The acid in vinegar. In very small amounts, it might add a slight sharpness or winey note. However, higher concentrations usually indicate over-fermentation during processing and result in an unpleasant vinegar-like flavor and aroma.

Looking for Lower Acidity? How to Manage Coffee Acidity

Feeling the effects of coffee’s acidity, perhaps experiencing heartburn or stomach discomfort? You’re not alone. To reduce coffee acidity, consider options like choosing darker roasts, selecting beans naturally lower in acid (often from lower altitudes like Brazil or Sumatra), utilizing brewing methods like cold brew, or adding milk or a specialized acid reducer to your finished cup. Some coffee brands also specifically market low-acid varieties.

Choosing Low-Acid Coffee Beans

Certain coffee origins and types are naturally lower in perceived acidity. Look for:

* Low-Altitude Origins: Beans grown at lower altitudes often develop less acidity. Examples include coffees from Brazil, Sumatra, India, or Nicaragua.

* Specific Varieties: While Arabica is generally more acidic, certain cultivars or specific lots might be lower. Robusta beans are typically lower in perceived acidity (though higher in bitterness/CGAs).

* Monsooned Malabar: An Indian coffee processed to reduce acidity through exposure to monsoon winds.

* Low-Acid Brands: Some companies specifically source and roast beans to minimize acidity.

Brewing Methods to Lower Acidity

The way you brew can significantly impact the final acidity in your cup.

* Cold Brew: This is a game-changer for acidity sensitivity. Cold brewing coffee drastically reduces its perceived acidity compared to hot brewing methods. Because extraction happens slowly with cold water over 12-24 hours, fewer acidic compounds are dissolved into the final concentrate, resulting in a much smoother, mellower taste.

* Espresso: While concentrated, the rapid extraction time of espresso can sometimes result in a less acidic tasting cup compared to slower drip methods, though this varies greatly by bean and technique.

* Avoid Over-Extraction: Brewing too long or with water that’s too hot can extract more bitter and sour compounds, increasing unpleasant acidity.

The Impact of Roast Level on Acidity Perception

As mentioned earlier, roasting directly impacts acid levels. Choosing darker roasts is a reliable way to get coffee with lower perceived acidity. The extended heat exposure breaks down many of the organic acids, including citric and malic acid, leading to a smoother, less tangy flavor profile, often emphasizing body and roast notes over bright acidity.

Tip: Adding milk, cream, or even a pinch of baking soda (an alkali) to your brewed coffee can help neutralize some of the acid, reducing the perceived tanginess.

Is Citric Acid Also Found in Tea?

Curious if your other favorite caffeinated beverage shares this acidic component? Yes, tea, including popular varieties like green tea and black tea, also naturally contains citric acid, although typically in different concentrations and alongside different complementary acids than found in coffee. Similar to coffee, the citric acid in tea contributes to its overall flavor complexity, often adding subtle tartness or citrus nuances depending on the specific tea type, processing, and brewing method. The overall acid profile and resulting taste, however, differ significantly between tea and coffee.

FAQs About Citric Acid in Coffee

Let’s tackle some common questions about citric acid and coffee acidity.

Does coffee have a lot of citric acid?

It varies, but citric acid is considered one of the major organic acids contributing to flavor, especially in bright Arabica coffees. While not usually the most abundant acid overall (chlorogenic acids often hold that title in green beans), its impact on taste is significant. Concentrations are typically higher in light roasts and certain origins.

Which acid is most dominant in coffee?

In green coffee, chlorogenic acids are generally the most abundant. However, during roasting, these decrease while others change. In terms of flavor impact for desirable acidity, citric and malic acids are often considered dominant contributors to brightness and fruitiness in high-quality coffees.

Does Starbucks coffee contain added citric acid?

Generally, standard brewed coffee or espresso drinks at Starbucks (and most coffee shops) do not contain added citric acid. The citric acid present is naturally occurring in the beans. However, some blended drinks, syrups, or food items sold there might contain added citric acid as a preservative or flavor enhancer – always check ingredient lists for specific products.

What coffee is naturally low in citric acid?

Coffees grown at lower altitudes (like many Brazilian or Sumatran beans) and Robusta varieties tend to be naturally lower in citric acid. Darker roasts will also have significantly less citric acid due to degradation during the roasting process.

Can you taste citric acid in coffee?

Absolutely. Citric acid is directly responsible for the bright, tangy, lemon-like, or grapefruit-like notes perceived in many coffees, particularly lighter roasts from origins known for bright acidity like Kenya or Ethiopia. It contributes a distinct sensory experience.

How does citric acid affect coffee’s pH?

Like all acids, citric acid contributes to lowering the overall pH of coffee, making it chemically acidic. However, the amount of citric acid relative to other compounds means its specific impact on the final pH number is just one part of a complex chemical balance. Perceived taste doesn’t always correlate directly with pH.

Is citric acid removed during decaffeination?

Most common decaffeination processes (Swiss Water, CO2, chemical solvents) primarily target caffeine molecules and aim to preserve the original flavor compounds, including acids like citric acid. While some minor changes to the overall chemical profile can occur, significant removal of citric acid is not the goal or typical outcome of decaffeination.

Does adding milk reduce the citric acid in coffee?

Adding milk doesn’t chemically remove citric acid, but it can significantly reduce the perception of acidity. Milk proteins (like casein) can bind with some compounds, and the fats and sugars add richness and sweetness that buffer or mask the sharp taste of the acids, leading to a smoother flavor.

Are there health concerns with citric acid in coffee?

For most people, the naturally occurring levels of citric acid in coffee pose no health concerns. It’s a common acid found in many fruits. However, individuals highly sensitive to acidic foods or those with conditions like acid reflux or GERD might find that the overall acidity of coffee (from all acids combined) can trigger symptoms.

Which coffee processing method preserves the most citric acid?

Generally, the washed (or wet) processing method is considered best for preserving and highlighting the inherent clarity and brightness associated with acids like citric acid. Natural processing introduces more fruit-derived compounds that can sometimes mask or alter the perception of specific acids.

Summary: Citric Acid’s Bright Role in Your Coffee Cup

So, the answer is a definitive yes: coffee inherently contains citric acid, a natural component contributing significantly to its vibrant flavor profile. It’s not an additive but a key player in creating those desirable bright, tangy, and citrusy notes that elevate many high-quality brews.

Remember these key takeaways:

- Natural Component: Citric acid is one of several important organic acids found naturally in coffee beans.

- Flavor Impact: It’s primarily responsible for bright, tangy, lemon/lime/grapefruit notes.

- Influencing Factors: Levels are affected by variety (Arabica > Robusta), altitude (higher = more), processing (washed highlights it), and especially roast (light > dark).

- Not Alone: It works alongside other acids like malic (fruity), chlorogenic (bitter), quinic (sour), and acetic (vinegar) to create the full acidic profile.

- Management: If acidity is a concern, opt for darker roasts, low-altitude beans, cold brew, or add milk.

Understanding the role of citric acid unlocks a new layer of appreciation for the complexity in your cup. What are your favorite bright, citric-forward coffees? Share your thoughts or questions in the comments below!